The Satellite Genesis: In the Beginning was Science Fiction

Satellites are an invisible yet integral part of modernity. In meteorology, communications, logistics, agriculture, and defence, to name just a few applications, the satellite industry generated $261 billion in revenues in 2016.[1] Despite its present value, its path from science-fiction to market maturation was fortuitous and far from a “sure thing.” From the mysterious radio signals detected on U.S. soil during WWII, to the misinterpretation of KGB intelligence, this essay series looks at the key events and milestones of satellite (and by extension rocketry) development. To what extent were satellites inevitable? Was satellite innovation a case of top-down, directed research, or was it more serendipitous?

Newton, from what I could gather, was the first to propose the idea of artificial satellites. Published as a thought experiment in A Treatise of the Systems of the World (1678), Newton’s Cannonball, as it has come to be known, first demonstrated the mathematical possibility of orbits.[2]

Two centuries later, science fiction writers, Jules Verne and Edward Everette Hale would resurface this idea in their depictions of artificial satellites launched into orbit.[3] Jules Verne’s De la Terre á la Lune (From the Earth to the Moon) in particular, would become the space-geek bible of sorts and go on to inspire the original pioneers of rocketry: Tsiolkovsky, Potočnik, Oberth, Goddard, Pierce, and von Braun.[4]

Satellites and rockets was lodged squarely in the realm of science-fiction until 1897, when Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a Russian maths teacher and a founding figure in rocketry, mathematically demonstrated the feasibility of rockets to launch spacecraft into orbit. In Investigating Outer Space with Rocket Devices, he derived the “Tsiolkovsky rocket equation,” calculated the minimal speed required to orbit the Earth, and demonstrated that this could be achieved by using a multi-stage rocket. His work did not garner much attention or serious consideration initially—this was six years before the Wright Flyer after all—and he was regarded as an eccentric and recluse. As we’ll see, this characterization of the rocketry pioneer as part dreamer, part science fiction writer, and part scientist would come to define rocket scientists of the early 20th century.[4]

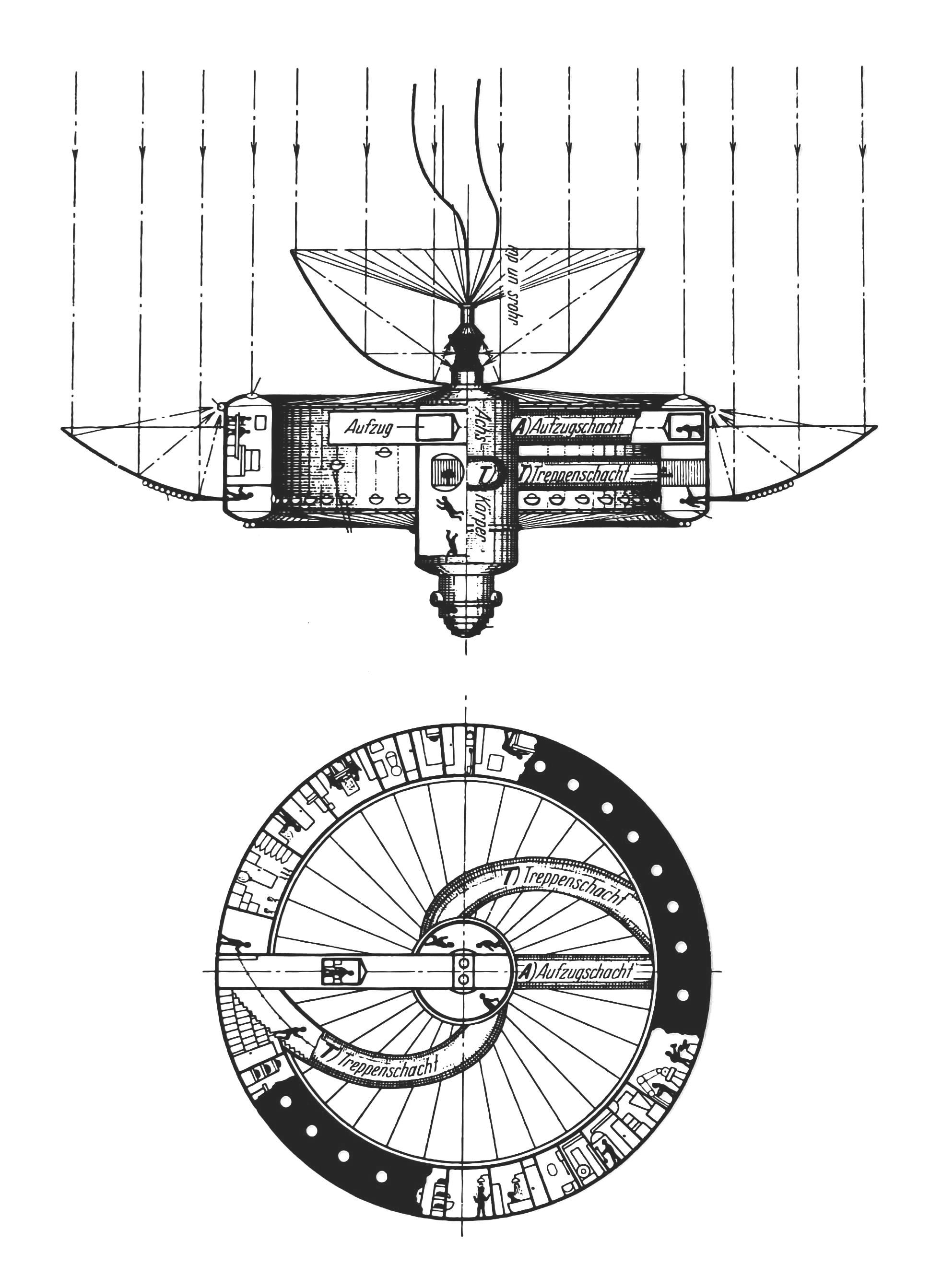

In 1928, Herman Potočnik, a Slovene rocket engineer proposed concrete ideas for space applications. In contrast to Tsiolkovsky, who believed space colonization as an inherent good and will lead to human immortality,[5] Potočnik was more practical. His book, The Problem of Space Travel: The Rocket Motor, put forth detailed designs for a space station, peaceful and military uses of Earth observation satellites, and describes space as a unique environment to conduct scientific experiments. But like Tsiolkovsky before him, his ideas were mostly ignored by his colleagues in the Austro-Hungarian scientific community.[4] His most ardent fans would come from the German amateur rocketry movement, the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (VfR - “Spaceflight Society”).[6]

To mainstream narratives, it still wasn’t clear whether spaceships were science-fiction or science-fact. One leading member of VfR, Hermann Oberth, who would go on to be known as another founding father of rocketry, had his doctoral dissertation rejected in 1922 by the University of Göttingen on account of it being too “utopian,” and its author nothing but a “romantic futurist.”[4] Even after WWII, when John Robinson Pierce, Executive Director of Bell Lab’s Research-Communications Division, first wrote about the potential benefits of communication satellites, it appeared in the Astounding Science Fiction magazine in 1952. It didn’t help that he was also a science fiction writer and published the article under his science fiction pseudonym J. J. Coupling.[7] To tug on the science fiction thread further, it was Sir Arthur C. Clarke, the British futurist, undersea explorer and science fiction author of 2001: A Space Odyssey, who first proposed the use of geostationary satellites (satellites in orbits that stay in the same position above Earth) as telecommunications relays in 1945. The geostationary orbit is now officially recognized by the International Astronomical Union as the “Clarke orbit.”[8]

Early spaceflight innovations were borne of grand narratives embedded in the scientific understanding at the time. Being careful to not read too much intentionality into these developments, as historic narrations are prone to do, two main things stand out: 1) The power of narratives and the 2) Lack of top-down direction or “experts”.

Jules Verne’s meticulously researched stories captured the imagination of the early space pioneers: Tsiolkovsky, Potočnik, Oberth, Goddard, Pierce, and von Braun all read Verne's From the Earth to the Moon. And in Oberth’s case, he re-read it to the point of memorization.[9] Of all the threads that tie these founding fathers of rocketry together, this is the one that stands out. To what extent Verne's work influenced theirs we can't be sure, but it certainly lends credence to the necessity of imagination in innovation. As Carl Jung postulated, “people don’t have ideas; ideas have people.” Perhaps the space dreams of these pioneers—whether planted by Verne or otherwise—"had" them sufficiently to persist in the face of overwhelming ridicule. Because to build an industry or category, by definition, means stepping outside of pre-existing boundaries.

Early spaceflight progress was marked by amateur bottom-up experimentation. There was no issued “objective” to the early research that was conducted, as much as science fiction depictions could be called an objective. There was little funding available initially as the ideas proposed seemed too far-fetched. Tsiolkovsky himself had to fund many of his early research, and had to take up position as a teacher to do so. So while President Kennedy’s “We choose to go the Moon” top-down promise is widely remembered as a defining moment of the space race, the early innovations should be remembered for its bottoms-up tinkering.

In the next part of this series, we’ll dive into the Nazi war machine and the fortuitous circumstances that led to the development of rocketry.

References

[1] Bryce Space and Technology. (June 2017). State of the Satellite Industry Report

[2] Newton's cannonball. (September 2019). Wikipedia

[3] Rocketry Through the Ages, Rockets in Science Fiction. Marshall Spaceflight Center

[4] John Bloom (2016). Eccentric Orbits: The Iridium Story.

[5] Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. (September 2019). Wikipedia

[6] Herman Potočnik. (September 2019). Wikipedia

[7] Donald C. Elder. Beyond the Ionosphere: The Development of Satellite Communications, Chapter 2. NASA History Series

[8] Arthur C. Clarke. (September 2019). Wikipedia

[9] Hermann Oberth. (September 2019). Wikipedia